As this year’s Australian Open approaches its final with only a handful of players, there are also only a handful of racket stringers left, and Kui Zhang is one of them.

Key points:

- Stringing a tennis racket requires precision and speed

- There are only a few dozen stringers skilled enough to work at Grand Slam tournaments.

- More than 500 rackets strung at Australian Open on busiest days

Coming from China as a member of the official stringing team, Mr Zhang is working around the clock at his second Australian Open.

“I start at 8am and finish around 8pm or even later. It’s very tiring but satisfying once the work is finished,” Mr Zhang told the ABC.

“After my flight arrived in Australia, I checked into my hotel and immediately started work. I had no time for sightseeing, it was all work.”

His teacher, former Australian Open player Sam Chan, was in the audience this year watching over his favorite players on court.

Over the past two decades, Mr Chan has worked at 17 Grand Slam tournaments, including all four majors, handling the rackets of the world’s best players, such as Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Serena Williams.

Only a few dozen have qualified to play Grand Slam tournaments

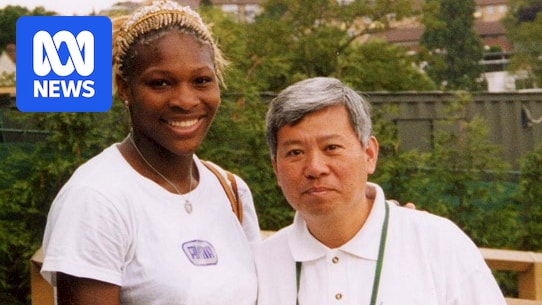

Sam Chan played for Serena Williams at Wimbledon in 2002. (Supplied: Sam Chan)

In the late 1970s, Mr Chan left his job as a fashion designer in London to become a professional stringer traveling to tournaments alongside his wife Corrie, who spoke six languages and worked in stringing room administration.

The 69-year-old said there were only a “handful” of people qualified to compete in Grand Slam tournaments.

“There are about 30 to 50 people in the world at this level, but usually it’s about 20 people who are always touring the world,” he told ABC.

“You need to be quick and accurate. You have to be good at both, but reaching a certain level is very difficult.“

Mr Chan said that at the Grand Slam level, stringers had to string a racket in 15 to 18 minutes, whereas if it was a racket for a player currently on the court, it had to be done in around 12 minutes.

Racquet stringing involves pulling the string through the holes of a racquet to a certain tension using a machine.

This is crucial for players who hit shots with centimeter accuracy: too loose or too tight and balls will fly or fall short.

“You have to know someone to get in.”

Sam Chan says a stringer needs to be “fast and precise” to work in Grand Slams. (Supplied: Sam Chan)

This year at the Australian Open, up to 500 tennis rackets pass through the stringing room every day.

But being one of those selected to work with the tools of the world’s best players is no easy feat.

“It’s not an open environment where people can apply to play roping (at a grand slam),” Mr Chan said.

“You have to know someone who can introduce you or someone who thinks you’re good enough to be invited – it’s a very closed business.”

Mr Chan said spars usually received a small remuneration for their work, but sometimes they were not paid at all.

“One thing a lot of people don’t realize is that in this business, they don’t get paid well,” he said.

“If you string at home or in a store your pay is better than if you string at tournaments it’s a very low pay.“

Mr Chan said that at most Grand Slam tournaments, players were paid around $200 a day, plus hotel and airfare costs, were often required to work more than 12 hours a day and sometimes had to skip meal breaks.

“When you die, someone else can step in.”

Melbourne stringer Kuankuan Wang with Sam Chan and his wife Corrie at the Australian Open. (Provided: Kuankuan Wang)

Mr Chan is now retired and living in Melbourne, but he hopes to bring more new blood into the business through teaching.

“When you die, someone else can step in,” he said.

“The tennis sector is losing steam a bit… but we still have a lot more tennis clubs than in other countries and a lot of tournaments for juniors compared to England; in England they don’t have enough facilities compared to here.”

Despite the low wages and intense work, many local tennis enthusiasts are still trying to get into the Grand Slam stringing business.

Kuankuan Wang is one of the few promising Chinese players in Melbourne. He teaches at a university by day and ropes in his tennis store in the evening.

Stringing tennis rackets is an art. (ABC News: Kai Feng)

His love affair with tennis began a decade ago, leading him to move and settle in the tennis capital of Australia.

“When I discovered tennis, I was studying at Xiamen University. Tennis was one of the optional subjects and I’ve loved it ever since,” he told ABC.

“I immigrated to Melbourne for the Australian Open. I continued my education from China, came to study, then immigrated and now I’ve settled down and have my own career.“

Although Mr. Wang is relatively new to the industry, he is already eyeing the grand slams.

“The main motivation comes from the love of tennis. It’s difficult to continue for a long time if you’re only here for the money,” he said.

“I’m a little new compared to the other stringers since this is my second year stringing, but my ultimate goal is to make it through all four Grand Slams.”