The last time I saw Rickey Henderson was in late September in the Athletics clubhouse as the final, sad home game at the Oakland Coliseum drew to a close.

I had known him since 1979, when he reached the big leagues in his first appearance with the A’s. He was 20 at the time and part of Oakland’s next-generation outfield consisting of Rickey, Dwayne Murphy and Tony Armas. It was the perfect outfield for talented young players at the time, and it cost the ever-precarious owner, Charlie Finley, less than $100,000.

More from Sportico.com

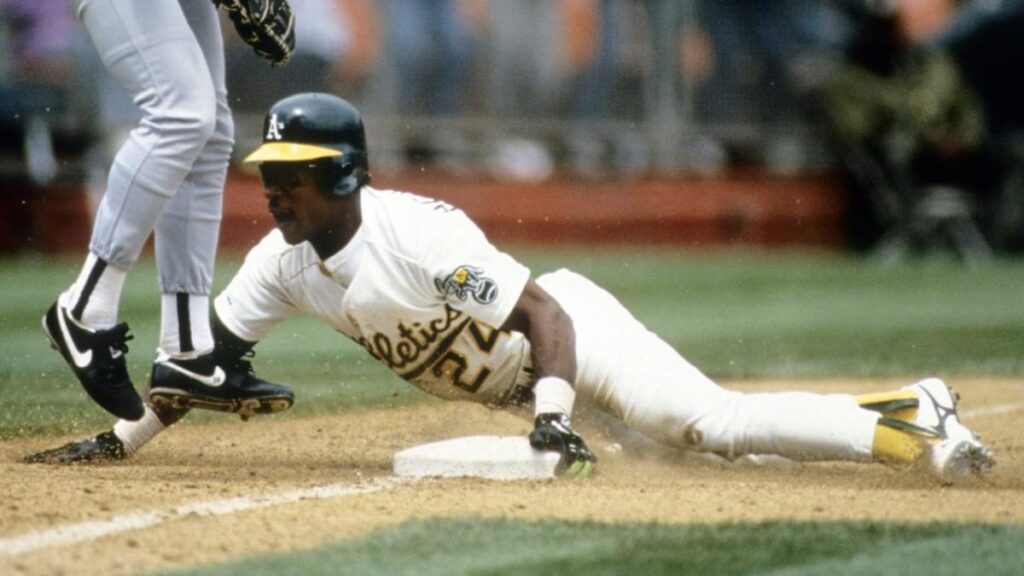

No one at the time knew who Henderson would become: the greatest base stealer and leadoff hitter in Major League Baseball history, earning $44.5 million over his 25-year career, a pittance in comparison of $51 million per season over 15 years. Juan Soto recently signed with the New York Mets.

That September day, Rickey was upset that the A’s were leaving Oakland, temporarily for West Sacramento next season, then perhaps for Las Vegas in 2028 or beyond. But he said that as a traveling coach, he intended to accompany them.

“It’s a real shame,” Henderson said. “Heartbreaking. I’m from Oakland and we lost everything. It’s almost like it’s going to be a ghost town. That’s what’s sad.”

Nothing was said Oakland baseball more than Rickey, I wrote at the time. He grew up there. He played at the high school dance there. Played for the A’s in this old building many times during his long career. And on Friday, he died there, at age 65, in an Oakland hospital, the victim of pneumonia and asthma that caused him to choke on his own fluids.

His death was a shock to those close to him because he seemed to be in perpetual good health.

“I still can’t believe it. He was a picture of fitness,” Ken Korach, the A’s longtime play-by-play announcer, said in a text message. “Rickey’s passing was a poignant final punctuation for the A’s last year in Oakland.”

Henderson’s death isn’t just about baseball loss in 2024 or the last few years before. He is the 17th member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame to die since the death of Al Kaline on April 6, 2020, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ten of these great men died within a year of Kaline, including Tom Seaver, Whitey Ford, Tommy Lasorda and finally Hank Aaron. It was the most games in one year in Hall history. This year alone, Henderson was joined in baseball heaven by Willie Mays and Orlando Cepeda.

Luis Aparicio, at 90, and Sandy Koufax, who turns 89 on Monday, are the oldest players still in the room. Former Commissioner Bud Selig is also 90 years old.

We have lost a whole golden generation of great players. This year also saw the passing of non-Hall of Famers. Fernando Valenzuela, Pete Rose and Luis Tiant, among others.

Henderson wasn’t that old by today’s standards. Neither do Tony Gwynn and Kirby Puckett, for that matter. Gwynn died at age 54 in 2014 after a long battle with the effects of parotid cancer. Puckett had a stroke before dying at age 45 in 2006.

These are the outliers. For others, time simply takes its toll.

Henderson played for nine teams during his seemingly endless career and brought his exciting style of play and winning methods to the A’s four times and the San Diego Padres twice.

In Oakland, former general manager Sandy Alderson said in a recent statement, “I traded Rickey twice and brought him back more times than that. He was the best player I ever saw play.

Some of these trades were because Rickey had deteriorated on his contracts and become a nuisance. But he was always an attractive player to bring back.

Midseason in 1989, Alderson got it again in a trade with the New York Yankees just in time for the A’s to sweep the San Francisco Giants in that earthquake-interrupted World Series. He dominated these postseasons, earning the American League Championship Series MVP victory over Toronto and hitting .474 in the World Series. He was 15 for 34 overall with nine walks, 11 stolen bases, including eight against the Blue Jays.

In San Diego, the late general manager Kevin Towers signed Rickey in 1996, and he helped the Padres make the playoffs for the first time since 1984. Rickey was then traded to the Angels in 1997. A few years later, when he left the Seattle Mariners. as a free agent, Towers received a voicemail from Rickey in the spring of 2001, George Will recalled in a recent Washington Post column.

“KT!” It’s Rickey! I’m calling about Rickey! Rickey wants to play baseball!

Rickey was known for referring to himself in the third person. Towers re-signed him on March 21, 2001.

It was Gwynn’s final season, ending with his left knee in such bad shape that he was relegated to pinch-hitting. But he could still hit, and when he reached the base manager, Bruce Bochy immediately replaced him with a pinch runner. During the penultimate game of that season against the Colorado Rockies at old Jack Murphy Stadium, Gwynn and Henderson both hit doubles. It was the last of 3,141 career hits for Gwynn and No. 2,999 for Henderson.

The next day was Gwynn’s last game and huge festivities were planned at the stadium. Out of respect for Gwynn – and I know this is a true story because I was there – Henderson walked up to Gwynn and asked, “Do you mind if Rickey gets his 3,000th hit during your last match? Because if you do, I won’t play.

Gwynn told Rickey to go.

In the first inning on October 7, 2001, Rickey led off with a bloop double to right field for hit No. 3,000 and immediately left the game. Gwynn pinch-hit in the ninth inning and grounded out in his final at-bat. Henderson would finish with 3,055 hits and a record 1,406 stolen bases.

Now they are both gone. But their legacy certainly remains.

“Nine different teams, one unforgettable player,” Alderson wrote. “Sandy will miss Rickey.”

The best of Sportico.com

Register for Sportico Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, TwitterAnd Instagram.