The battle for college athletes’ rights is playing out on multiple fronts: the federal courts, the halls of Congress, state legislatures and across the National Labor Relations Board.

The NLRB front takes center stage Tuesday in Los Angeles, where the Los Angeles area office will hear a case involving allegations that USC football players and men’s and women’s basketball players would be employees within the meaning of the law. National Labor Relations Act. The NLRB named U.S.C.the Pac-12 and the NCAA as “joint employers” and accused them of misclassifying players as “student-athletes.”

At issue in the case, brought by the former UCLA football player and advocate for college athletes Ramogi Humais whether athletes participating in these revenue-generating sports should instead be classified as employees.

In September 2021, in the months following the Supreme Court ruling favor of college athletesallowing them to profit from the use of their name, image and likeness, NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo issued a statement informing all field offices that she considers “certain players” from colleges to be employees of the institutions for which they play.

In February 2022, Huma, president of the National College Players Assn., filed separate charges against USC and UCLA, as well as the Pac-12 and the NCAA. The UCLA charges were dropped — it’s harder for the NLRB to establish jurisdiction over a public institution — while the USC charges moved forward.

Here’s what you need to know about this case and its enormous potential to force a systemic overhaul of college sports.

If athletes in these sports become school employees, how will the athletes benefit?

USC football players take the field before a game against Arizona at the Coliseum on Oct. 7.

(Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times)

Simply put, they would receive all the benefits enjoyed by anyone employed under the law: minimum wage, social security, overtime, workers’ compensation, other health and safety protections, and labor protections. workplace against racial discrimination and sexual harassment.

Players would also have the option to unionize and bargain collectively with schools to improve their conditions.

“Right now, if players decide to negotiate, the employer is not obligated to negotiate in good faith,” Huma said. “They can wrongfully end opportunities for college athletes without the players having any recourse.” This puts them in a better position to attempt to bargain collectively.

What do schools think about this subject? Should I be skeptical of what schools say?

The NCAA’s worst-case scenario has always been that college athletes become employees, forcing schools to share with players revenue that traditionally went toward coaches’ and administrators’ salaries and new facilities.

The schools, the Pac-12 and the NCAA should rebut the NLRB general counsel’s position, arguing that referring to USC athletes as employees would result in conflicts under Title IX, immigration, IRS policy and workers’ compensation laws. They also called it a potential violation of the 1st Amendment, requiring them to approve a new label for athletes they disagree with.

The groups are asking Congress to save them with a law specifying that athletes are not employees.

At a recent U.S. Senate hearing on the future of college sports, Huma was on a panel and was frustrated by how he heard the issue being described — but not surprised.

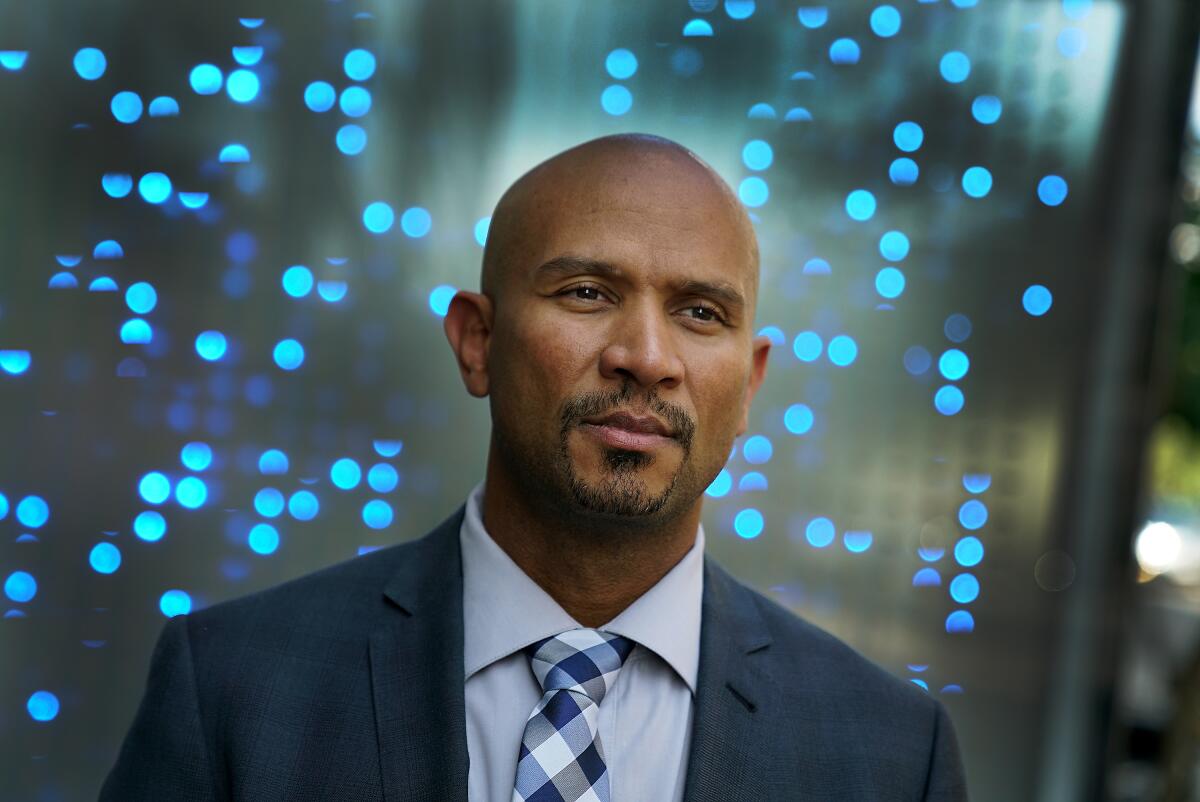

Ramogi Huma, a former UCLA football player and advocate for college athletes, filed allegations regarding USC with the NLRB.

(Kirk McKoy/Los Angeles Times)

“There has been a targeted effort to frame employee status as bad for college athletes,” Huma said. “It was not an accurate description of the realities before us.”

On the one hand, Huma said, speakers at the hearing were talking about Division II and Division III athletes or Division I athletes from non-profit sports also being classified as employees and forcing the cancellation of programs at all levels due to spending. But the NLRB’s case focuses only on USC football and men’s and women’s basketball.

“They say we talk to a lot of college athletes and they don’t want to be employees,” Huma said. “Well, what do you tell them?” It was the same with NIL, it would lead to sports being cut, and once boosters started paying players we wouldn’t have enough money for other sports. To date, after two years of NIL, I have not heard of any school discontinuing sports due to NIL misappropriation of funds.

At one point during the hearing, Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) expressed shock at the idea of college athletes being fired.

“Our position is that players can already be fired and they are,” Huma said. “Look at Deion Sanders in Colorado. Deion clearly announced in the press that he was going to run away (from the players). AKA, he was going to fire them. There is no unfair dismissal or protection in this process.

It’s worth noting that the same schools and coaches that rail against the transfer portal might be able to set limits on the portal through collective bargaining.

Why will this be any different than when Northwest football players tried to unionize?

Huma was also a key advisor to Northwest football players who attempted to unionize in 2014. In that case, the regional office said the players were employees, but the national office did not assert its skill.

“At Northwestern, we had to innovate at this time, in a more hostile and unprecedented public opinion environment,” Huma said. “Between the Supreme Court and Jennifer Abruzzo’s memo released right after the decision, Congress is really the NCAA’s last hope in terms of trying to remove players from employee status. If players are treated equally under labor law, they are clearly employees of the schools.”

What structure will the hearings take and when will they be completed?

This week’s hearings will focus on pretrial motions and subpoena issues. No testimony will be heard before December 18-20. The hearing could last until the end of February if necessary.

If the regional office confirms the initial charges, the file will be transferred to the national office.