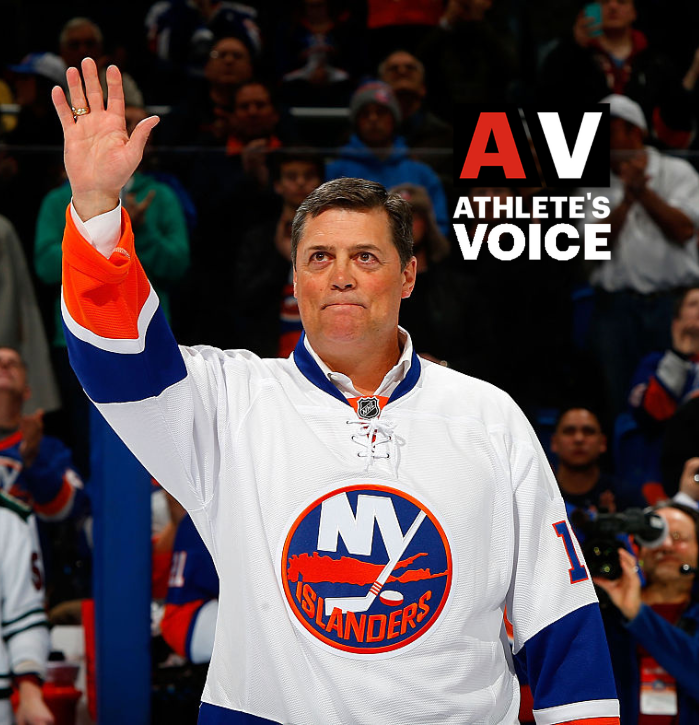

Jim McIsaac/NHLI via Getty Images

* * * * *

Today, it is not possible to have a discussion about sports technology without including athletes in that conversation. Their partnerships, investments and support help fuel the space – they have become major players in the sports technology ecosystem. The Athlete’s Voice series highlights the athletes who are leading the way and the projects and products they are influencing.

* * * * *

Hockey Hall of Famer Pat LaFontaine was a New York institution, first playing for the Islanders and Sabers before finishing with one season as a Ranger. During those 15 years, he scored 468 goals, added 545 assists and holds the all-time record of 1.17 points per game among American-born players. LaFontaine’s number 16 was retired by the Sabers and he was included in the league’s 2017 list of the 100 greatest NHL players of all time.

Although LaFontaine had a great career, it ended sooner than he had hoped. He’s suffered a half-dozen permanent concussions, but estimates the actual total could be double that. The neurologist who treated him throughout his career – Dr. James Kelly, a professor at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus who previously held a leadership position at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center – became a friend .

“Jim and I have become very close over the last 25 or 30 years,” LaFontaine said. “It was the doctor who cleared me to play, and he was the one who told me, ‘OK, that’s enough.’ I am extremely grateful to him.

LaFontaine, now 58, and Kelly are also now co-founders of a new company, Valor Hockey, which made a very popular helmet. The axiom of valor received a five star rating from the renowned Virginia Tech safety testing lab, the first new helmet to achieve this top rating since 2017. Atlantic Amateur Hockey Associationwhich is affiliated with USA Hockey, is the first league to partner in the promotion of the Valor helmet which costs $299.

On Valor’s origin story. . .

It actually all started when Dr. Kelly and I were looking at doing something in 2004. A company had a material that was 40% more absorbent and able to deflect and absorb impacts, I think, better than PPE at the time, which was the mainstay. What we found out was that they filed an intellectual property lawsuit with the material. So we tidied it up a bit.

We started talking again around 2016 or so. There was an opportunity with another impact material that we were studying. The irony was that (the helmet) was originally designed by a guy named Jose Fernandez. He did X-Man, he did Batman, he did Ironman. It was more like, “If you could create a cool, futuristic design of what a hockey helmet is in the future.” »

We spoke with a gentleman, designer and now partner, named David Muskovitz. So David did the engineering and the final design, but we took an initial design and said, “OK, how can we make this safer?” » And how can we make it work really well, scale really well? And then, how can we be sure we can make it? And above all, secure it?

We created a monocoque, which is a one-piece hull. I think one thing is important, I mean 98%, 97% of all helmets are two-piece shells, which we found interesting. All NFL, Motocross, Lacrosse and Major League Baseball (helmets) – why are they one piece shells? So we came up with a slogan “beyond the traditional safe”, because in the field of hockey, two-piece cases are traditionally safe. Then we discovered that making a one-piece injected polycarbonate shell was not easy with this kind of design. But if you build a very good one-piece and a very good two-piece, the one-piece will always perform better and be safer. For what? In fact, the impacts will be distributed more evenly compared to a two-piece.

On the shape of the helmet. . .

Dr. Kelly described this very well. We literally took this design and created smoother, slightly rounded edges on the sides of the helmet, then the back and finally the front. We created a lower profile with a small deviation angle. The way he says it is, so take a cue ball, then take a Rubik’s cube, and the cue ball hits the cube and it kind of grabs it, squeezes it, spins it and sometimes breaks it because it has more flat spaces. Well, take another cue ball with a billiard ball and hit it. And if it has more slightly rounded, smoother edges, it will deflect, ricochet and peek.

PREVIOUS

FOLLOWING

On minimizing the scale of impacts. . .

You won’t stop a concussion – no one will – but now, knowing the science and testing, you can minimize the damage. And over the course of someone’s career, you think about some of these catastrophic successes, these great successes, and then you think about these daily squeeze successes, over a period of time, the brain in the head is not built to support them.

I don’t know exactly what the measurements are, but if someone says you could get a level 3 concussion with a helmet, and potentially a level 2 or 1 concussion (with another helmet), that’s significant. You accumulate this over time. Minimizing damage makes a huge difference to livelihoods.

On the helmets he wore as a player. . .

Dr. Kelly said something very profound to me along the way. We didn’t have the testing or the science behind linear and rotary testing – we didn’t have that back then. That’s exactly how it was back then. Helmets were what they were. But if it were rated today, it would probably be a zero to one star.

Now knowing what a five-star (helmet) is and the impacts it takes to distribute the force load, Jim actually told me, “I can, professionally and publicly, be able to comfortably say, after having learned what I know about science. and testing, that you would most likely have taken between 50% and 60% less damage over the course of your career. And for me, it’s profound.

On his own experience with concussions. . .

I’m here to tell you the story because I lived it. I suffered from post-concussion syndrome twice. I went through an extremely dark time where things got really scary and depressing, and I really didn’t see any light at the end of the tunnel. I know what can happen if you hit your head enough and you can do damage.

Luckily, my brain found its way back. I was able to rediscover that enthusiasm and excitement. Dr. Kelly was willing to let me go back, but warned me, “If you take another one, you’re probably going to go through a (dark) period again because there’s a threshold you cross.” What used to take 10 days to two weeks to recover now takes you months. I’ve probably had about six to seven (concussions) documented – when I broke my jaw, we never documented it, but I guarantee you I had a concussion. And then I probably had a handful more shots where I saw stars but we didn’t count them. I’m probably in the double digits, 10, 12, for concussions.

I went through six months (of rehab) twice. The second time wasn’t as bad. But even then, there was a part of me relieved that I didn’t have to make that decision, and then a part of me had to give up something I’d loved since I was a kid. So it was still difficult to manage. But I heard something really profound. I read this book called Legacy about the All Blacks rugby team. There’s a quote in there that says if you are a true servant and leader of your sport, then you have a responsibility to leave it in a better state than you found it. My wife had a hard time watching my son play. He had a few concussions, and then she couldn’t watch anymore, having experienced what her husband went through. We now have a three-year-old grandson named Patrick. And you know what, I know that if he chooses to play hockey, there will be safer products for the next generation.

“On how hockey shaped him”. . .

I’m grateful for what we had when I was playing. It’s something to take into account and (ask) how can we create an evolution towards where security needs to go and I think that should be a natural thing to do anyway. Look, if I hadn’t retired after 15 years of concussion, I wouldn’t have had any service or purpose for doing this. So I always believe that, in life, your experiences, good, bad or indifferent, whether you realize it or not, prepare you for what comes next in your life.

I believe your experiences shape you in your service and purpose. And hockey has always been a stepping stone. I am grateful for what sport has done for me. But it put me in a place in my life where everything I learned from those experiences taught me how to give back in a focused, meaningful, and service-oriented way. And I have a mantra in my life, whether it’s my foundation or what we do with Valor: “Score your goals when you’re young because when you grow up, life is about assists.” »

On the values instilled by hockey and in the Valor brand. . .

As a player I was lucky, and it was a privilege and an honor to play pro for as long as I did and represent my country. Gaming was my life, and it still is. I say that even though I play less, the game still lives in me. Character lessons, life lessons, values, life skills, leadership, teamwork, overcoming adversity, gaining enough discipline, friendships, relationships, all of these Things you learn in the sport of hockey are still so important. a part of who you are in your life going forward, which is really a big part of what the brand is built on.

The Declaration of Principles that we launched with the National Hockey League – the tip of the spear, that north star – and we succeeded in getting the global hockey community to endorse the values and principles to aspire to live by. Part of the Valor brand therefore relies on these statements of principles and brings them to life, whether in products, programs, technology or services. From my point of view, it is very important that sport plays a role in our society and in our next generation. Creating a positive and safe environment is therefore part of this.