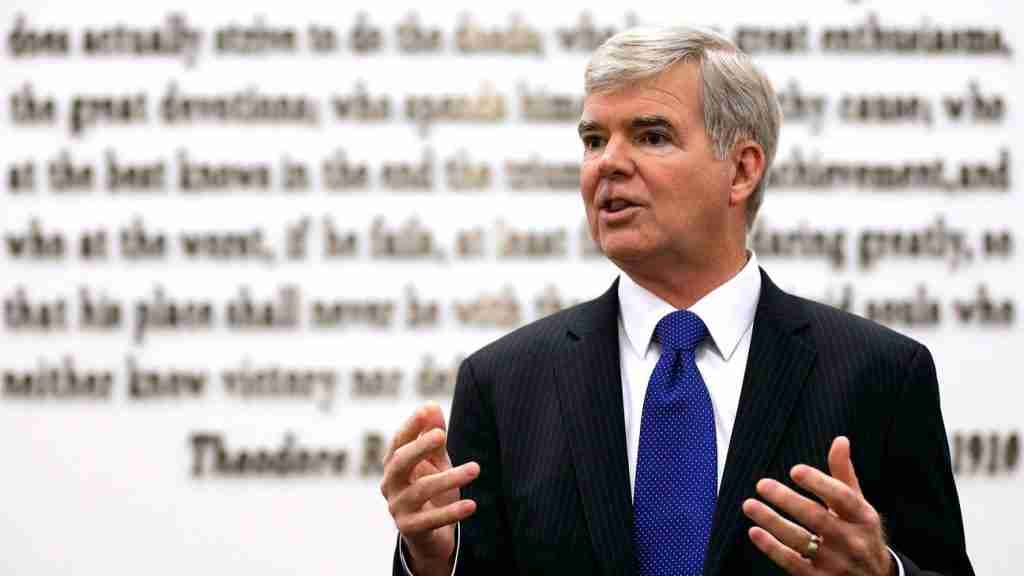

WASHINGTON — NCAA President Mark Emmert urged Congress to restrict college athletes’ ability to earn money from sponsorships, telling a Senate committee Tuesday that federal action was needed to “maintain uniform standards in college sports” in the context of player-friendly laws approved in California and considered in other states.

Last fall, the NCAA announced it would allow players to “profit” from the use of their names, images and likenesses and is working on new rules that it plans to reveal in April. According to the NCAA’s timeline, athletes could take advantage of the endorsement opportunities starting in January.

At the same time, more than 25 states are considering legislation to force the NCAA to allow players to earn money from their personal brands, in an effort to address inequities in the multibillion-dollar college sports industry. California passed a law last year that grants broad endorsement rights to players, and it will go into effect in 2023. Other states could grant those rights as early as this year.

The NCAA’s concern, echoed by Big 12 Commissioner Bob Bowlsby, who also testified Tuesday, is that sponsorship deals for athletes would have a negative impact on recruiting, with schools and promoters in states with athlete-friendly laws using the money to entice players to sign with certain schools.

“If these laws were implemented, they would give some schools an unfair advantage in recruiting and open the door to sponsorship deals being used as recruiting incentives. This would create a huge imbalance among schools and could lead to corruption in the recruiting process,” Emmert said. “We may need the support of Congress to help maintain uniform standards in college sports.”

Emmert’s comments are similar to those the NCAA, Big 12 and Atlantic Coast Conference have communicated to Congress through highly paid lobbyists. The Associated Press found that the NCAA and the two conferences spent $750,000 last year lobbying on Capitol Hill, in part to amplify their concerns about the need for “guardrails” on sponsor compensation for athletes to avoid destroying college sports as we know it.

Sen. Jerry Moran, a Kansas Republican and chairman of the House Subcommittee on Manufacturing, Trade and Consumer Protection, said he was not inclined to act until the NCAA reveals its new rules.

“I wish Congress had been able to provide the NCAA and the athletes with the opportunity to find a solution. … The ability of Congress to do that is a challenge,” Moran said in an interview after the hearing. “The next step is to see what the NCAA is able to present to us in April.”

NCAA critics say there is ample evidence that recruiting is already corrupt — pointing in part to the federal criminal case involving shoe companies paying basketball players to attend schools they sponsor — and that letting players make money won’t create major problems, the NCAA predicts.

Ramogi Huma, executive director of the National College Players’ Association, which advocates for athletes’ rights, said that under current NCAA rules, 99.3 percent of football’s top 100 recruits choose teams from Power 5 conferences.

“Power conferences have advantages, and they consistently recruit the best recruits,” Huma said. “They’ll continue to recruit. The reality is you’re not going to change recruiting by limiting player opportunities.”

Huma said that once states begin granting sponsorship rights to players, Congress will not be inclined to take away those rights, “and we will have the opportunity to see that NCAA sports will still be strong and that everyone will listen.”

There was bipartisan agreement among senators during the hearing that athletes should have access to sponsorship opportunities and that some regulations are necessary.

Emmert has not completely escaped lawmakers’ anger at the system he presides over.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn, a Republican from Tennessee, blasted Emmert for the NCAA’s handling of sexual violence against women. She also discussed the case of James Wiseman, a top NBA prospect who left school after being suspended for giving $11,500 to his mother by Memphis coach Penny Hardaway to help pay for moving expenses. Hardaway donated the money before becoming Memphis’ coach.

Blackburn said the NCAA’s lack of consistency and transparency in the Wiseman case has eroded confidence in the organization’s ability to handle player benefits issues.

“I think a question that must go through the minds of many student-athletes and their parents is how can they trust you to do this? » said Blackburn.