Aliyah Boston (South Carolina), Paige Bueckers (Connecticut), Dana Evans (Louisville) and Rhyne Howard (Kentucky) arrived at the NCAA women’s March Madness tournament “bubble” in San Antonio this month as part of The Next Generation of NCAA StarsThese women have earned their chance to dance on the biggest stage in college basketball, with all the pomp and circumstance that comes with it.

But here to salute the best college basketball players in the country were amenities and accommodations — all provided under the auspices of the NCAA — which were vastly inconsistent with those offered to their male counterparts in the men’s tournament bubble in Indianapolis.

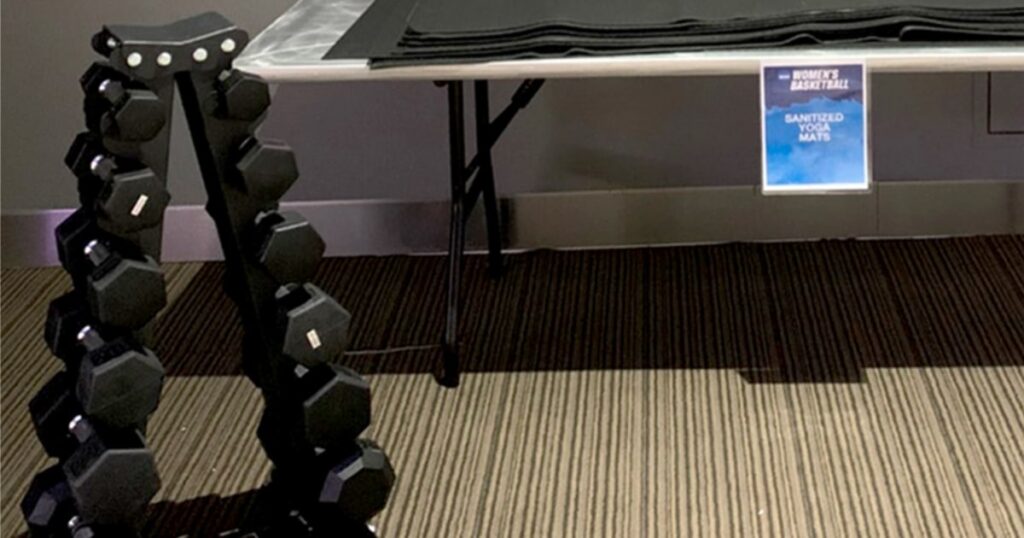

The “weight room” for these Division I athletes consisted of a a single, embarrassing stack of six pairs of weights and a handful of yoga mats stacked on a folding table. The men’s side, by comparison, looks more like the floor of Planet Fitness.

As images of bodybuilding facilities went viral on social media, other disturbing information slowly surfaced. Unlike the rich buffets served in the men’s bubblewomen received small prepackaged mealsWomen’s teams also received less reliable Covid-19 antigen tests, while men’s teams received the gold-standard PCR tests. Even the women’s “goody bags” were less impressive. Rather than facilitate full media access in a year when coverage has already been hampered by the pandemic, the NCAA cut costs further by opting to not having photographers at the women’s tournament for the first two rounds. However, he managed to gather enough photographers to publish thousands of photos opening matches of the men’s tournament.

Unable to refute the clear difference in equipment, The NCAA initially hid behind a statement They blamed the pandemic’s “controlled environment” and claimed the gap between workout facilities was due to a lack of space in the women’s bubble. But that claim was quickly debunked. by a video Posted by Sedona Prince, a sophomore at Oregon. She put it succinctly: “If you’re not upset about this problem, then you’re part of it.”

The NCAA has long been part of the problem. Indeed, the protections provided by Title IX to shield student-athletes from this type of disparate treatment do not apply to the NCAA.

You read that right. More than two decades ago, NCAA vs. SmithThe Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the NCAA was not required to comply with Title IX rules because it is a nonprofit organization comprised of member colleges and universities, and while most of those institutions receive federal funds, the NCAA does not. The Supreme Court left open the possibility of a case in which Title IX might apply to the NCAA, but no such case has ever been decided by a court.

The protections provided by Title IX to shield student-athletes from this type of disparate treatment do not apply to the NCAA.

Immediately following the NCAA v. Smith case, the NCAA publicly stated its commitment to comply voluntarily with Title IX mandates, even though it is not legally required to do so. Today, the NCAA proclaims on its website She strives to establish “an environment free of gender bias.” But her words don’t always translate into meaningful action, and the NCAA has been exploiting this legal loophole for years.

In fact, the NCAA initially encountered considerable resistance to Title IX. In the 1970s, The NCAA has exerted strong pressure restrict the application of Title IX to college sports, ironically fearing that it would be a burden on men’s teams. In 1976, the NCAA unsuccessfully filed a lawsuit challenging the legality of Title IX, arguing that it should never apply to athletic programs.

While the NCAA has supported women’s sports as they have grown in popularity, there’s no denying that it has never given the women’s team the same support it gives the men’s team. One need only look at the court itself to see that the NCAA has failed to use its most powerful promotional tool to promote the women’s tournament: the trademarked “March Madness” logo that adorns center court for men’s games. no brand restrictions By banning the NCAA from using the March Madness brand to promote the men’s and women’s tournaments, it inexplicably decided to use it only in the men’s tournament.

Most egregiously, the NCAA has consistently deemed women’s basketball unworthy of its greatest financial reward: the bonuses paid to conferences for their teams’ NCAA tournament victories, which in turn trickle down to colleges and universities. From 1997 to 2018, the NCAA doled out more than a billion dollars to the top five men’s conferences (the Big Ten, Atlantic Coast Conference, Big 12, Southeastern Conference and Pac-12). By comparison, the NCAA has not contributed a single cent to a single women’s tournament win since its inception in 1982.

The NCAA’s likely justification for the different treatment? The fact that the women’s basketball tournament doesn’t generate enough revenue. But the NCAA also did not disclose What are the revenues and costs of the women’s tournament, let alone how they compare to the men’s tournament. Even if the numbers showed that the NCAA couldn’t economically justify the same level of bonuses for the women’s tournament, it never provided a good-faith rationale for why it couldn’t reward victories in a more limited way. That would at least give women a piece of the revenue pie. The NCAA, however, recently confirmed that it is not pushing for any changes in the bonus structure.

As others have done arguedThe NCAA’s refusal to reward women’s tournament victories sends a message that it views women’s teams as less deserving, at least financially. That message has always been unacceptable. The message sent in the wake of the San Antonio debacle is even more troubling.

As the NCAA acknowledges in its own Title IX Guidance DocumentGender equality isn’t just about money; it’s also about benefits and opportunities. That includes benefits to players’ health, safety and well-being, especially since the NCAA decided to hold March Madness amid a pandemic.

There is nothing fair about using the most powerful brand to promote the men’s tournament but not the women’s. There is nothing fair about using a handful of free weights versus a full-service fitness center. There is nothing fair about providing high-level testing to ensure the health and safety of male student-athletes, but relegating women to the less reliable option (especially given the NCAA’s choice to host the tournament). women’s tournament in a state which recently put Covid-19 safety on the back burner).

Unsurprisingly, the inequalities between the men’s and women’s teams have sparked a strong reaction from players, coaches, fans and the media. Sponsors and investors have also reacted. Dick’s Sporting Goods Announcement his willingness to bring “truckloads of fitness equipment” to the rescue of San Antonio. Orange Theory Fitness also offers to open its studios for private sessions and to deliver floor and weight training equipment.

These companies understand what the NCAA seems to ignore: Women’s sports have value, especially in the commercial marketplace, and that value increases with investment, opportunity, and support. The growing numbers and audiences of women’s sports support this conclusion. In 2019, ticket sales increased across the country during the regular season. A sellout crowd and 3.6 million viewers I watched the 2019 Women’s Championship game, which prompted ESPN to broadcast every women’s game that season for the first time.

In response to his public shaming, the NCAA Solved Weight Room Problem By finding the resources it previously lacked, seemingly overnight. But a Band-Aid is not a real solution. To fix a systemic problem, the NCAA must make systemic changes. To do that, this momentum for change cannot be allowed to fade.

For years, the NCAA seemed to operate under the assumption that it could get away with treating women’s basketball like a lesser sport. That is no longer the case. If the NCAA cannot be held legally accountable, it must be held socially accountable. Member institutions should lead the charge, because they have a legal duty to their student-athletes under Title IX. Let’s not forget that Prince, the Oregon player, did something when institutions and the NCAA failed her. Title IX, however, places the responsibility on institutions to ensure equal opportunity. Players should never be forced to shoulder that burden.

Sponsors and investors should also make supporting the women’s tournament a regular practice, not a one-off sporadic operation when the public is paying attention and the marketing moment is right.

Finally, the NCAA itself must take concrete and lasting action. Its behavior in San Antonio is a scandal and a disgrace. This should be the last time the value of elite NCAA women athletes is so blatantly denigrated. Until it does, the NCAA’s commitment as the supposed guarantor of Title IX protections will remain woefully shallow.