MIDDLEBURY — As hundreds gathered May 12 for the grand opening of the first Reproductive Justice Mini Golf of course, they were faced with a scene full of juxtaposition.

Colorful golf balls, a popcorn machine and painted T-rex dinosaurs glowed with the iconic roadside Americana camp. But another layer revealed a more nuanced landscape.

Behind a T-rex, in a hole labeled “Care Work”, the players were required to hold a doll while putting their golf ball in a makeshift kitchen. In another hole, a skeleton hung at the end of a hospital corridor. Beyond, a hole looked like a prison.

“The history of incarceration is a history of violence: forced separation of children, shackling during childbirth, loss of parental rights, forced sterilization, criminalization of black mothers, detention of immigrants, total rejection of bodily autonomy “, reads the sign at Hole 10. “You are about to enter a 6′ x 9′ replica of a solitary confinement cell, where many of these forms of violence take place of State.”

According to project manager Carly Thomsen, the course – which she says is the first of its kind – was designed as a feminist tool to learn about reproductive justice and the systems that deny it.

For many of its creators, the kitsch aesthetic of the course coupled with the injustice it depicts has created a game that seems – especially in the context of recent anti-transgender legislation and the overturning Roe v. Wade – even more precisely and strangely “American” than ordinary miniature golf.

Each of the courses 11 holes focuses on a different topic related to reproductive justice, according to Thomsen, assistant professor of gender, sexuality and feminist studies at Middlebury College.

Thomsen said that since many of the theoretical ideas that contextualize reproductive justice are only accessible through dense academic texts, the mini-golf course aims to translate some of the field’s core arguments into a more accessible model.

Friday, as players roamed the hand-built greens, launching balls into landscapes constructed to replicate sites where reproductive problems occur — a hospital, a kitchen, a courthouse, a classroom, a bar – they were confronted with manifestations of feminist ideas that were anchored in the physical.

Rayn Bumstead, director of design for the minigolf course, said the project’s approach encourages players to think about the architectures and geographies of reproductive justice.

“The places where reproductive injustices occur are all around us, which means the possibilities for resistance are also all around us,” Bumstead said in a press release.

On the sixth hole, for example, players approached two doors, one of which led to a abortion clinic while another hid a crisis pregnancy center, which offered an infinitely more difficult putting trajectory. With its two doors designed to be virtually indistinguishable, this hole expresses the impact of crisis pregnancy centers, which aim to discourage people from having abortions.

Isa Pérez-Martín, a student and research assistant who became involved in public feminism organizing last year, said she built the sixth hole to “express the idea of chance.” For example, you often don’t really know what you’re getting into with crisis pregnancy centers. … (They) seem to be helping you, but not really.

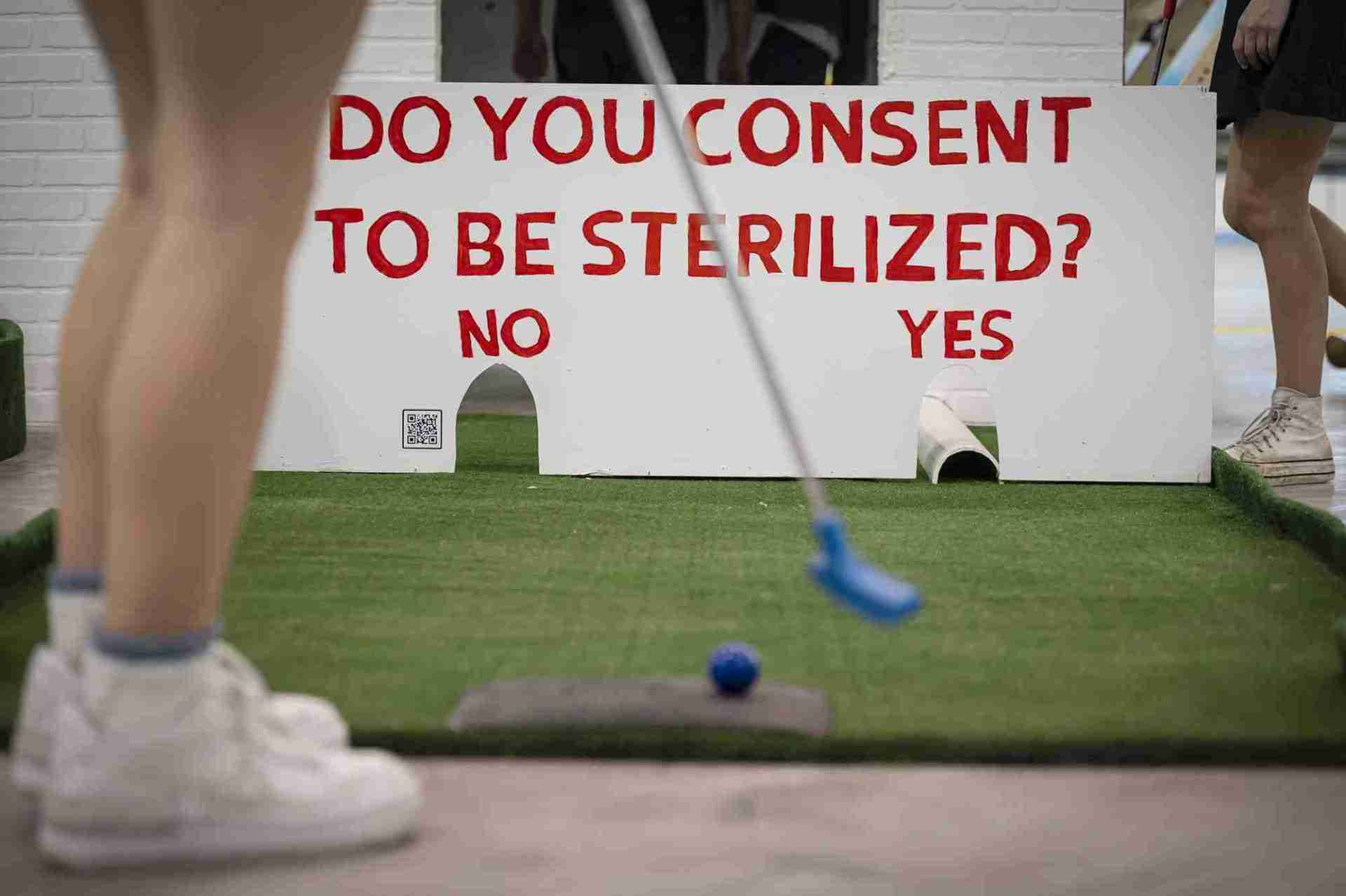

On the 10th hole, players were faced with the same question that incarcerated people in TennesseeFor example, we asked: “Do you agree to be sterilized (in exchange for a reduced prison sentence)?”

At this hole, if players passed through the tunnel indicating the answer “yes”, their ball could pass through the replica prison cell without a hitch. If players answered “no”, they encountered obstacles that made escaping the prison cell much more difficult.

After thinking about this choice, the players were led to visualize a visiting stand. There, one could use a makeshift landline phone to listen to stories recorded by Lily Shannon, a student in Thomsen’s class, and Susan Stanfill, Shannon’s mother, both affected by Stanfill syndrome. incarceration when Shannon was 10 years old.

“Reproductive justice is also about motherhood in general,” Shannon told VTDigger. “One of the reasons we shared this was my hope that people would have less judgment and stigma toward incarcerated mothers.”

Maureen Hill, a mother who took her three children to the opening, stood outside the prison hole while her children were vaccinated through the cell. On the way to the event, Hill said she reminded her children that it was OK to ask questions about what they would see.

“I think what’s cool is that for kids, developmentally, they’re going to understand some things, and other things they might not be quite ready to talk about.” , Hill said. “That’s great. They’ll ask the questions they want to know the answers to.

Sponsored by the Center for Public Feminismthe project was born from the original idea of Thomsen, who used game creation for teaching feminist and queer theory for years. It came to fruition through extensive collaboration with art studio technician Colin Boyd, Bumstead, students, and other partners at the college and beyond.

The physical golf course, which occupies half of Middlebury College’s Kenyon Arena, was designed and built primarily by nine Middlebury students enrolled in “Feminist Building,” a course taught by Thomsen and Boyd.

Over the course of a semester, students in this class devoted hours of work to imagining, planning, and assembling life-size mini-golf holes, while students in another class – Thomsen’s “Politics of Reproduction” – generated educational content and art to contextualize. each hole.

The collaboration extended to Denver, Colorado, where two Metropolitan State University students designed one of the holes, which was then constructed at Middlebury by project participants. Trail Blazers program through Vermont works for women, a nonprofit economic justice and job training organization. Students in gender studies courses at Providence College and Hamilton College also created artwork for the course.

“I think a big part of this whole project is how many different stakeholders and individuals and partners really wanted to be a part of this,” said Rhoni Basden, director of Vermont Works for Women.

When the course came to life that opening Friday, it looked, as one child shouted as he ran past the “Care Work” hole, like a tiny version of the world.

“We set up the golf course to make it feel like you’re moving through a community or a city,” Thomsen said. “These are all sites where reproductive injustices occur. They are also, it means, sites where activism for reproductive justice could shine through.

The mini golf course is free and will be open to the public from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays until July 15.