Caravaggio’s Malta (Micaela Parente-Unsplash)

It was said that the Italian master Caravaggio was offended by a bet concerning a tennis match. Unable to control his temper, he drew his sword and slashed it through Ranuccio Tomassoni, killing him in a Roman street.

It is questionable whether this was murder in the heat of battle: duels were banned by papal decree and it is suspected that it was exactly that, but the fight was covered up by the seconds of the two men to protect everyone from further censorship.

Caravaggio was lucky to be protected by his talent. This meant he had friends in high places. Bringing him to justice was not easy, but he had to leave the Eternal City without delay.

An unintended consequence of this struggle was how it sent the artist on a forced journey into exile – and inspired a series of his works.

Artists and their journeys – and their travails, in Caravaggio’s case – are the subject of a new book by Highgate-based social historian Travis Elborough.

Travis’ previous works include his History of the Routemaster Bus, The Player’s Long Record, Parks and Pleasure Gardens, Spectacles, and Abandoned Architectural Oddities.

In The artist’s journeyit focuses its attention on a selection of artists who have become synonymous with a place, or who have found their canon expanded through movement, travel and travel.

“A change of scenery and the opportunity to experience a different environment and get to know unfamiliar faces and customs can stimulate new creativity,” he says.

“The journey itself, a springboard to an artistic elsewhere… painters tend to be the itinerant type. They are constantly looking for new things to dedicate to paper or canvas.

Caravaggio’s case was one of forced exile, as Travis explains.

“Caravaggio was impetuous and prone to drawing knives to settle disputes,” he writes. “But it seems more than likely now that Caravaggio and Tomassoni were engaged in a pre-arranged duel.

“The duel was a crime punishable by death in Rome, the tennis match was probably a cover-up by their respective seconds to avoid censorship.”

Girls on the Bridge, 1899, by Edvard Munch at Åsgårdstrand. (Incamerastock-Alamy Stock)

Caravaggio was given refuge by the powerful Colonna family and it was while resting at his estate, 20 miles from Rome, that he painted an image of David clutching the head of Goliath, and was considered as an appeal for clemency to Scipione Bhorgese, who supervised the pope. justice.

But as Travis explains, in addition to his powerful friends, the artist had powerful enemies and it was deemed prudent for him to put more distance between himself and the long arms of the law.

He headed south to Naples, then under the control of the Spanish kings. “Despite his status as a killer on the run, Caravaggio continues to be sought after as an artist,” he adds. He was commissioned to create a huge room for a new church in the center of the city.

Caravaggio couldn’t stand there – new allegations around paying an assassin to kill an enemy meant Rome didn’t seem far enough away.

He headed to Malta, which was then essentially an island run by a heavily armed church and led by the Knights Hospitaller of Saint John of Jerusalem. Perhaps he hoped that by joining them he would obtain a pardon. What Caravaggio did do was make a living painting for the friars, and he had high hopes of being accepted into the order, which put him beyond the reach of the Pope. He eventually fell out with the monks and headed for Sicily, before ending up in Naples, where he died of a fever at just 38 years old.

Other artists evolved under far less pressure than the 16th-century purveyor of grandiose biblical scenes.

Travis considers Cézanne in Provence (as well as van Gogh in the same place), Dali in Manhattan, Katsushika Hokusai and his various views of Mount Fuki, Paul Klee in Tunisia, Turner in the Alps and Matisse in Morocco. Many were drawn by the light, the thrill of discovery and often by personal circumstances – travel abroad for the European artist could mean an affordable lifestyle, allowing them to focus on creating and not not keep food on the table and a fire in the fireplace. .

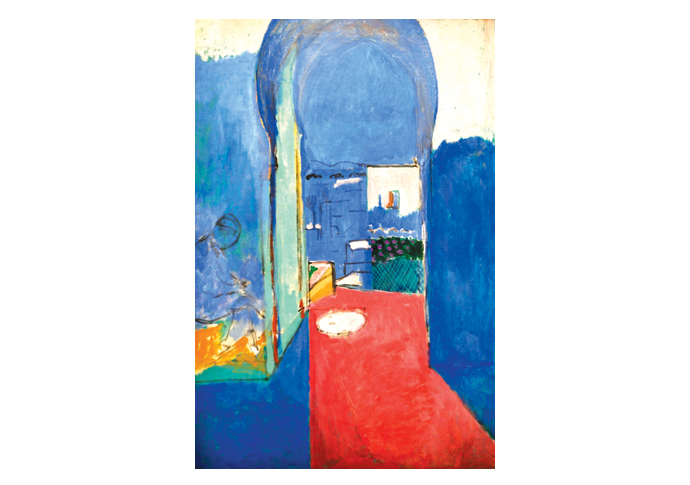

Entrance to the Kasbah, 1912, Henri Matisse. (Agefotostock-Almy Stock)

For Claude Monet, a trip across the Channel led him to paint some of the best-known scenes of London ever committed to canvas. It was not an artistic desire that pushed him to install an easel on the quay, but rather the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.

Keen to avoid conscription, he traveled to London and his stay allowed him to capture the city’s lifeblood, the fuel that powered the empire: the mighty River Thames.

“Monet was drawn to the banks of the London River, its quays and bridges,” explains Travis. “During his stay he haunted the banks of the Thames and completed three studies.”

One was the Houses of Parliament bathed in fog from Joseph Bazalgette’s recently completed Victoria Embankment. Monet was sufficiently seduced by the city to return three times 30 years after his first visit.

Artists traveling to new places would also innovate in terms of style. One of these pioneers was the Antwerp artist Alexander Keirincx, who was commissioned by Charles I to paint 10 views of his castles in Yorkshire and Scotland. The artist had completed four by the time the Civil War broke out.

“His images, shaped by the turn toward greater veracity in Dutch landscape painting, set new standards for realism,” adds Travis.

His skills mean that, six centuries later, it is possible to precisely locate the places where he installed his easel.

Above all, Travis concludes that artists are drawn to places for many reasons – but once there, the chosen location becomes an indissoluble connection to the work produced.

“A notable number of birds here have been attracted, like migratory birds, to the same places over and over again,” says Travis.

“Over time, this location will then become synonymous with the artist himself or will be seen retrospectively as characterizing a key period in his production.”

• The artist’s journey: the journeys that inspired the great artists. By Travis Elborough, White Lion, £20