Diego Maradona, the Argentine who became a national hero as one of football’s greatest players, playing with mischievous cunning and extravagant control while pursuing a personal life full of drug and alcohol abuse and problems with health, died Wednesday in Tigre, Argentina, in the province of Buenos Aires. . He was 60 years old.

His spokesman, Sebastián Sanchi, said the cause was a heart attack. Maradona had brain surgery several weeks ago.

The news of the death sparked a wave of mourning and remembrance in Argentina, becoming practically the only topic of conversation. Such was his stature – in 2000 FIFA, football’s governing body, voted him and Brazilian Pele the sport’s two greatest players – that the government declared three days of national mourning.

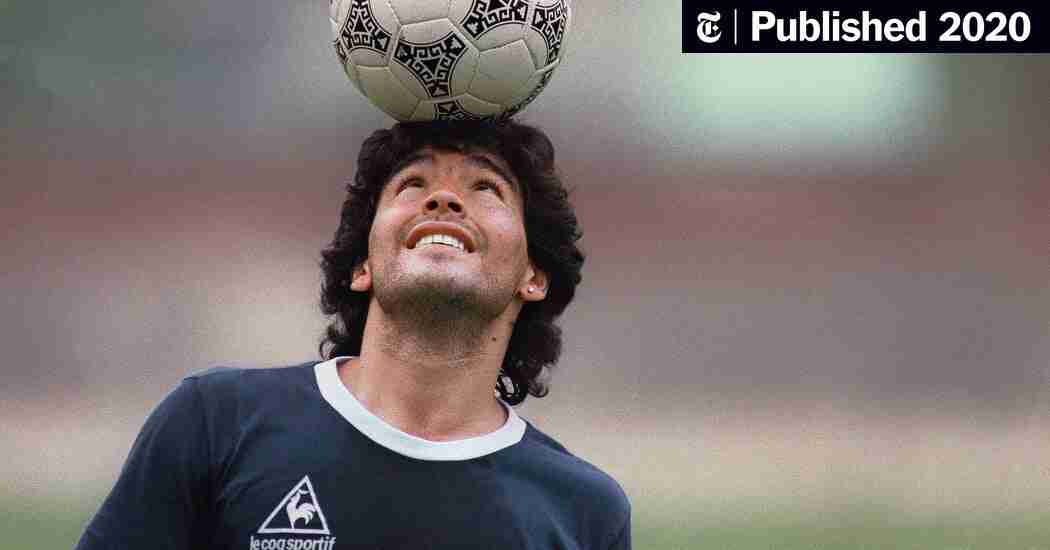

At Maradona’s feet, the ball seemed to obey his commands like a pet. (He was said to do with an orange what others could only do with a ball.) And he played in a sort of bright camouflage, appearing sleepy for long periods before asserting himself in moments of drowsiness. urgency with a fascinating dribble, an astonishing pass or stab.

Wearing a playmaker’s traditional number 10 jersey, Maradona led Argentina to the soccer world championship in 1986, scoring one of the game’s most controversial goals and one of the most celebrated in space of four minutes during the quarter-finals against England.

All the fame and infamy that marked his career and life were on display in that quarter-final match on June 22, 1986, when Argentina faced England at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City. The tension caused by the Falklands War between the two countries four years earlier persisted.

Six minutes into the second half of a scoreless match, Maradona dove into the England defense and slipped a short pass to a teammate. The ball ended up at the foot of England midfielder Steve Hodge, who sent a pass back to his goalkeeper, Peter Shilton, only to see the predatory Maradona intercede. Although he was only 5 feet 5 inches tall, Maradona jumped high into the air and sent the ball into the net.

He did not use his head, as it seemed at first, but rather his left fist, a maneuver forbidden by any footballer other than the goalkeeper. The Tunisian referee should have ruled out the goal but, perhaps not having seen the offensive, he did not do so.

Maradona later gave conflicting accounts of what happened. At first, he said he never touched the ball with his fist; then he said he did it by accident; then he attributed the goal to divine intervention, to “the hand of God”.

This infuriated the English.

“Eudent and unapologetic, Maradona mocked innocence, speaking of the ‘hand of God,'” Brian Glanville wrote in his book “The Story of the World Cup.” “For England, it was more like the hand of the devil.”

Four minutes later, Maradona scored again, finally giving Argentina a 2-1 victory. His second goal came after a 70-yard dribble by five English players and a final feint past Shilton to power the ball into an empty net. Deftly, he changed direction like a slalom skier going from one gate to another.

In his book “The Simplest Game,” Paul Gardner describes the run as “10 seconds of pure, unimaginable soccer skill to score one of the greatest goals in World Cup history.”

In the 1986 final, a pass from Maradona through the middle of the West German defense gave Argentina a 3-2 victory. “No player in the history of the World Cup has ever dominated the way Maradona dominated Mexico-86,” Gardner wrote.

Maradona threatened to force his way into the 1990 World Cup – collecting a loose ball, feinting a defender and passing through a thicket of legs to assist on the only goal of a last-16 victory against Brazil. In the semi-final, against Italy, the host team, Maradona scored the penalty that gave Argentina the lead by winning the penalty shootout.

It was Maradona in his glory. The match was played in the noisy port city of Naples, where Maradona had played professionally and led Naples to two Italian League titles. Boldly, he asked the supporters present to encourage Argentina rather than Italy.

But there was no more magic for the 1990 final against West Germany. Maradona was bruised after being repeatedly fouled and was missing several prominent teammates, who had been suspended for committing flagrant fouls. Argentina lost 1-0 from the penalty spot.

The Italians at the Olympic Stadium in Rome booed Maradona every time he touched the ball. After all, he had knocked Italy out of the tournament. Afterwards, he bitterly accused that the penalty had been given in retaliation for Italy’s early exit.

While the legend of Pelé became internationally revered, Maradona’s ability to surprise and frighten developed a darker side when he became addicted to cocaine while playing in the 1980s.

In 1991, he tested positive for cocaine while playing for Napoli and was suspended for 15 months. His behavior became erratic. In February 1994, he fired an air rifle at journalists outside his summer home in Argentina.

Later that year, he was kicked out of the World Cup, hosted in the United States, after testing positive for a cocktail of stimulants. As he got older, he apparently needed a boost of energy for his tired legs or desperate help losing weight.

His thick musculature having morphed into an unhealthy build, Maradona was hospitalized in Buenos Aires in April 2004 with what doctors described as a weakened heart and acute respiratory problems. He then entered a psychiatric hospital there and, in September, left for rehabilitation treatment in Havana.

His many health problems also included gastric bypass surgery to contain his weight and treatment for alcohol abuse. As a spectator at the 2018 World Cup in Russia, Maradona appeared to collapse and was treated by paramedics as Argentina scored a dramatic late victory over Nigeria to advance to the second round of the tournament.

Speaking to an Argentine TV channel in 2014, he said: “Do you know the player I could have been if I hadn’t taken drugs?

He continued: “I’m 53 and I’m going to be 78 because my life hasn’t been normal. I lived 80 years with the life I lived.

The complexity of his personal life was such that, according to media reports, he was the father of eight children, including two daughters with his then-wife Claudia Villafañe (they later divorced), and three children born while he was in Cuba. is undergoing treatment for his cocaine addiction.

His survivors include these daughters, Dalma and Gianinna, as well as three children from other relationships: Diego Armando Maradona Sinagra, an Italian soccer player; Jana Maradona; and Diego Fernando Maradona.

Diego Armando Maradona was born on October 30, 1960 in Lanus, Argentina, and grew up in the Buenos Aires slum of Villa Fiorito, where he began playing soccer in dusty streets with the ingenuity of a kid. By age 15, he had turned professional. (In his autobiography, he wrote that he became such a talented player in his youth that opposing coaches sometimes accused him of being a midget as an adult.)

He went on to play with European clubs Napoli and Barcelona and, in 2010, coached Argentina at the World Cup, hosted in South Africa, although his team suffered an embarrassing 4-0 defeat to Argentina. Germany in the quarter-finals.

He enjoyed a career as a traveling coach, managing club teams in Argentina, the United Arab Emirates and Mexico. In September, he was hired to coach the Argentine club Gimnasia y Esgrima in La Plata. On his 60th birthday, he attended his team’s match against Patronato, but left early in what became a 3–0 victory, prompting questions about his health.

When he entered a clinic in La Plata on November 2, his doctor, Leopoldo Luque, said Maradona was suffering from depression, anemia and dehydration. He then underwent brain surgery for a subdural hematoma, bleeding that accumulates in the tissues surrounding the brain and can be caused by head trauma. Dr. Luque told reporters that the injury was likely sustained in an accident that Maradona did not remember.

His death left Argentina and the football world in deep grief.

Pelé tweeted: “I have lost a great friend and the world has lost a legend.”

Napoli, his former Italian club, said in a statement: “We feel like a boxer who has been knocked out.”

Argentine President Alberto Fernández said of Maradona: “You took us to the top of the world. You made us very happy. You were the best of all.

And Reuters recalled the words of Pablo Alabarces, a professor of popular culture at the University of Buenos Aires, who once described Maradona’s bringing Argentina to the 1986 World Cup title as a national stopgap for a country reeling from economic crises and a humiliating defeat in the 1982 Falklands War.

“In our collective imagination,” Alabarces said, “Diego Maradona represents a certain glorious past. He is a symbol of what we could have been.

Daniel Politi contributed reporting.