The letter writer was exasperated, as so many people so often are, by America’s insistence on using its own word to describe the game that almost everyone calls football.

“It seems a real shame that, in its reporting on Association football matches, the New York Times, along with all the other newspapers, persists in calling this match a ‘socker’,” writes the writer , a certain Francis H. Tabor, declared in time. “Firstly, there is no such word, and secondly, it is extremely ugly and undignified. It was 1905, and it was proof that the perennial debate over “What’s wrong with America?” » did not begin at this World Cup, nor at the one that preceded it, but a quarter of a century before a World Cup existed. Irritably complaining about American usage – only to see Americans react immediately – turns out to be a sport almost as popular as football (or football) itself.

The latest analysis of this question comes from a much-discussed academic article recently published by Stefan Szymanski, an economist, professor of sports management at the University of Michigan and co-author of “Soccernomics.” In his analysisSzymanski points out that the word football actually started in Britain and continued to be used happily there – right alongside “football” – at least until the 1970s, when a surge of bad humor and anti-Americanism made it virtually radioactive.

“I’m English, I’m in my fifties and I remember, as a child, football being a perfectly acceptable word in the UK, without being this big Americanism no-no that it has become,” he said. Szymanski said in an interview. . “There are so many people who seem completely ignorant, as if this is entirely an American invention, and so I wanted to set the record straight.”

Among other things, he pointed out, Matt Busby, the manager of Manchester United in the 1950s and 1960s, wrote an autobiography, “Soccer at the Top,” and a biography of the famous player George Best was called ” George Best: The Inside. History of Football Superstar.

But while the two terms coexisted seemingly harmoniously abroad, the opposite was happening in America. Of course, by the beginning of the 20th century, the United States already had its own type of football, called “soccer.” It’s a sport, outsiders like to point out, in which people mostly do things with their hands. But it doesn’t matter for now.

In those early years, a parade of highly enthusiastic Britons ventured across the Atlantic in an effort to popularize football – then known in England by the official title “association football” – as a more civilized alternative. Times articles from this period reflect both a kind of delighted curiosity about the sport and great confusion about what to call the sport.

At that time, British football was already divided into two types. One was association football; the other was rugby football, known as rugby.

According to Szymanski, the term “football” was already in use in Britain, perhaps having started in Oxford and Cambridge as a shortened form of the word “association”. The students there liked, for some reason, he explained, to add the infantilizing diminutive “um” to random words. (Rugby, under this system, had been abbreviated to “rugger”, a term still widely used. Even today the English sometimes call football “footie”, but that is another matter).

Discussing this exciting new sport in 1905 and 1906, the New York Times used the term “football” as a useful shorthand, especially in headlines about space. But only sometimes. Other times it was spelled socker. Sometimes we called it football, but we put it in quotation marks. Other times he used “association football”, called it “football football” or “English football”.

An October 10, 1905 article described the efforts of Sir Alfred Harmsworth, an aristocratic London publisher, to “send a body of experts to American colleges” to teach them the proper way to play “socker.”

“It is believed that if the game is properly introduced to soccer fans through major universities,” the article states, American-style soccer “will ultimately play a secondary role to the ‘socker’ style of play.”

Big chance. But the article also noted, for good measure, that “English soccer players say American college soccer is brutal and unremarkable.”

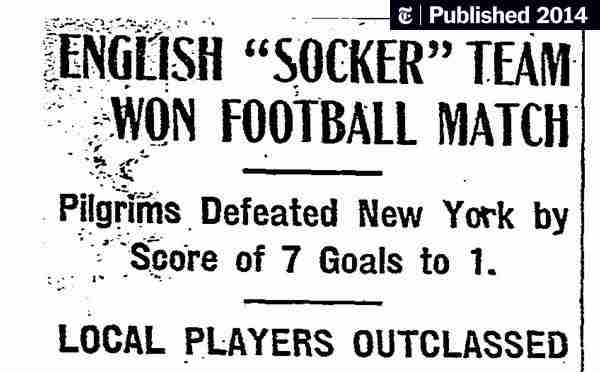

Then, on October 22, in an article describing a game between “the English Pilgrim Association football team” and the “All-New York Eleven,” whoever they were, the Times threw in a large dose of semantic confusion in the mix with its text. big title: “The English team “Socker” won a football match.” The Times then merrily stumbled around for a while, using “socker” and “football” interchangeably. The word, whatever its form, did not excite all its readers.

Days after Tabor’s attack on the word “socker” in 1905, another Times reader, Lawrence Boyd, published a indignant response – although, confusingly, it seemed to be responding to something other than Tabor’s actual point of view.

“Can I ask Mr. Tabor how he expects his word ‘football’ to be pronounced? Boyd wrote. “If spoken as written, it would be more than ever a reminder of socks.” He added: “’C’ before ‘e’ has the value of ‘s’, with almost no exceptions. »

After those difficult times, the Times finally settled down, dropping the k, dropping the word “association,” dropping the word “football,” dropping the quotation marks. It was football. A 1914 article referred to “50,000 British football fans” who attended a match between Chelsea and Bolton Wanderers in England.

For much of the century, Szymanski said, Britons would not have minded being called soccer fans. The problem arose, he said, in the 1970s and 1980s, when the sport became a force in the United States under the leadership of the now-defunct North American Soccer League.

It threatened people, and the English in particular, he said, and caused them to launch into violent speeches about America’s heinous and perverse tendency to do things differently from others and then claim that she was superior.

“I think the rest of the world finds the concept of American exceptionalism — ‘We give it a different name because we’re better and different than you guys’ — very irritating,” he said. “But that’s not what happened here.”

His article, although apparently definitive, did little to dampen the enthusiasm of the anti-football brigade.

“It’s called FOOTBALL,” a British blogger, Anonymous Coward, posted this month on an Internet forum devoted to this very subject. “We British invented the game, so why only our American cousins call it SOCCER.”

To which another poster, from Australia (a country that also calls it football), replied: “check your MORAN dictionary” (sic).