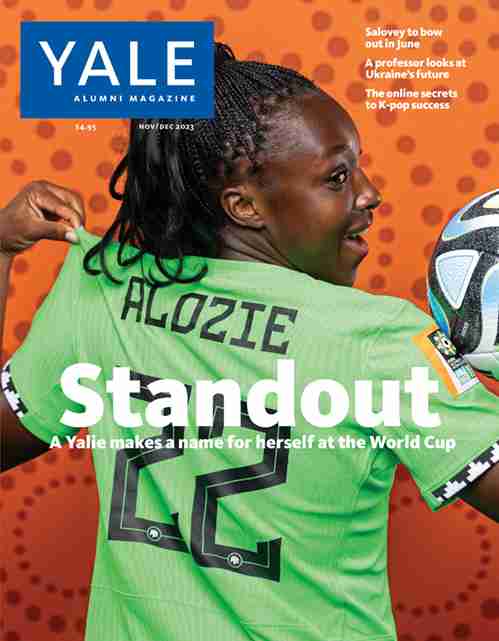

Among the many stories emerging from this summer’s Women’s World Cup, it’s difficult to miss the enthusiasm for a certain American member of the Nigerian team. Headlines exploded: “From the lab to the World Cup: Meet soccer player and scientist Michelle Alozie,” “Meet Michelle Alozie, the Nigerian star pursuing a career in medicine” and “Michelle Alozie dazzles in new photo” .

A month after Nigeria’s elimination from the tournament, on a Wednesday in September, Michelle Alozie ’19 was back in the daily life of a “football scientist.” She had just made a short trip from the practice fields of the Houston Dash, her professional soccer team in the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL), to Texas Children’s Hospital, where she works as a research technician in a laboratory that tests various novels. chemotherapies to treat pediatric leukemia. “We hope that the research we do on a smaller scale can scale up to a larger scale and then into clinical research,” Alozie says.

Later in the week, she would travel to Louisville, where her Dash picked up a crucial season-ending victory before returning to Texas for another action-packed week. “Personally, I’m exhausted by the time I get home from practice,” says Aerial Chavarin ’20, Alozie’s former teammate at Yale, who currently plays professionally in Mexico. “I’m not at all surprised that Michelle is able to make this work: she has always worked very hard and focused on her goals, on and off the field.”

While waiting to send samples from the lab, Alozie reflected on a summer that saw her become one of the most recognizable faces of the Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand. It was a summer that propelled her to international fame. “I blew up a little quicker than I thought I would,” she says. “I really feel very grateful for the platform and hope I can be a role model for everyone who is looking to work in science but wants to pursue a different passion, love or dream of theirs.”

Michelle Alozie was born to Nigerian parents in Apple Valley, California, in the Mojave Desert northeast of Los Angeles. She took up soccer at a young age, winning national championships with club teams and setting high school records in her hometown. She could have played at any number of Division I universities, but she knew she was interested in both a career in medicine and a professional career, and she decided Yale was a place where she could do both. “They really convinced me that I could make the best of any situation I found myself in,” she says. “Even though it’s not necessarily a school – or even a league – that produces a lot of professional athletes, I could still be the start of it.” »

In New Haven, the 5′ 6″ forward immediately stood out. She was named Yale’s top offensive player her freshman year and Ivy’s co-offensive player of the year as a junior. That year, 2017, Yale posted its best record in over a decade. She was named to the All-New England team. And just as a side note: she got the most votes.

Then, two games into what should have been a victory lap of a senior season, Alozie suffered a serious ACL injury that kept her out of action for nearly a year. After graduating from Yale, she played one more season at Tennessee with her eligibility remaining.

But her time at Yale, where she specialized in molecular, cellular, and developmental biology, only solidified her commitment to an unconventional path in medicine. Alozie found inspiration in Alan Dardik ’86, his senior year research mentor; he had studied computer science at Yale College, then became a surgeon-scientist at the Yale School of Medicine, focusing on vascular diseases. “He really showed the kind of fluidity that is possible in medicine,” she says. “It gave me some peace of mind knowing that even though my path will be very, very different, I can still make it my own.”

After her injury in 2018, Alozie attempted to enter the NWSL college draft, but she was not selected. She finished her season-long tour with Tennessee, then signed a deal with a Kazakh professional team. She performed in the early months of 2020, until the COVID-19 pandemic derailed her budding career.

But she had taken the first step into playing beyond college, as had several others who were on Yale’s roster in 2017. Along with Chavarin, who was drafted into the NWSL in 2020 and still plays professionally, Carlin Hudson ’18 became Yale’s top pick in 2018, and Noelle Higginson ’20 played for Louisville’s NWSL team before attending law school.

“I say this is the era of smart schools, because the best players want the highest academic institutions,” says current Yale head coach Sarah Martinez. “They have their athletic goals, obviously playing professionally, and I think being able to see that that can be done without sacrificing other professional goals has really elevated our conference as a whole.”

It’s a boom that coincides with the continued growth of women’s football. The NWSL is now in its eleventh year, more than doubling the longevity of any previous women’s professional league and setting new attendance records in each non-pandemic year. In 2023, an average of 10,000 fans attended each match: a growth of more than 100% since the creation of the league. The Women’s World Cup, which once had 24 teams, expanded to 32 teams for the first time this year.

In 2021, Alozie was still on the outside looking in. Then came a leap of faith, and it produced a series of big breaks. She contacted a former club teammate from her teenage years who played for the Houston Dash, who in turn connected her with the Dash coach for a spot on the practice squad. “My sister lives here in Houston,” she said. “I just showed up, literally crashed at her house, crossed my fingers and prayed that I could make the Houston team.”

And the pieces started to fall into place. A few months later, the Nigerian national team traveled to the United States for a series of exhibition matches ahead of the Tokyo Olympics. They were missing a number of players due to visa processing delays. With games coming up in Houston and spots to fill, Nigerian head coach, Randy Waldrum, himself a former head coach of the Houston Dash, attended Dash practice and discovered Alozie.

Two days later, Alozie made his international football debut against Jamaica as a member of the Nigerian national team, known as the Super Falcons. Three days later, she scored her first goal against Portugal. And in the same week, she was tasked with defending American star Megan Rapinoe in their final friendly match. “She brings such toughness on both sides of the ball,” Houston Dash general manager Alex Singer said. “I would hate to play against her.”

“Our FroCos at Yale asked us to write a letter to ourselves in five years,” says Alozie. “And on that letter, I wrote, ‘Oh, I’m going to break a scoring record at Yale.’ And then I said I would be part of the Nigerian national team in five years. It took a little longer: it took six years. It was perfect timing that they were literally in the city in where I was, and everything lined up really well.

Later that summer, Alozie signed a contract with the Houston Dash as a replacement player during the Olympics, before agreeing to a more permanent deal. Since that fateful week, she has been a key member of the Houston Dash and the Super Falcons. In June 2023, she was named to Nigeria’s roster for the World Cup as Nigeria prepared to face a tough group consisting of Canada, Australia and Ireland. Canada and Australia were considered the top ten teams according to the FIFA rankings; Nigeria was ranked 40th before the tournament. (Alozie wasn’t the only Bulldog at the World Cup; Reina Bonta ’22 was on the Philippines’ roster.)

“I don’t think it really hit me until I was in Australia. We were trying on the swimsuits for the first time, taking pictures and everything,” says Alozie. “I don’t know if it was imposter syndrome or an out-of-body experience. But it was definitely surreal that something I’ve dreamed of for as long as I can remember came true. The dream didn’t stop there. Nigeria became one of the exciting Cinderella stories of this tournament, going undefeated in their group to advance in upset fashion, including a dramatic 3-2 win over co-hosts Australia. In the round of 16, the Super Falcons remained tied with England (the eventual runner-up of the world) throughout the match before losing on penalties at the end.

Alozie started every match and was one of the few to play every minute for Nigeria, becoming a fan favorite with her aggressive play and charismatic presence. “She represented Yale, Nigeria, Houston Dash and her family with incredible pride,” Martinez said. “She has absolutely become a household name, not only among Yale fans, but around the world.”

That’s when she “exploded,” as Alozie described it. Suddenly, his face was splashed across Nigerian and international publications, covering his intertwined goals in football and medicine. “She has such confidence in herself that I really think she’s blossoming now,” Singer says. “I think it made perfect sense that she would end up leading the team on the world stage. Everyone could see who she was. The scientific journal Nature covered his story; his followers on Instagram and TikTok now number in the hundreds of thousands. “In college, we talked about our dreams and our aspirations on the field,” says Chavarin. “Seeing her accomplish hers with such class and gifts is inspiring.”

But this Wednesday in September, Alozie was back in the laboratory, refocused on her research mission. As an NWSL season comes to a close, Alozie normally works full-time at Texas Children’s until the seasonal cycle begins again, where she sets her sights on the Paris Olympics next summer. “I just hope my body is healthy and I can play football for as long as possible. And then once I see a dip or feel a little dissatisfied with my dream, I definitely have to hunker down and start studying for the MCAT again,” she says with a laugh. “But right now, I’m happy with where I’m at. Happy to focus on football. I’m happy to be in this lab and make a difference wherever I can.