During the first half-century of his career, Robert Jay Lifton published five books based on long-term studies on seemingly very different subjects. For his first book, “Thought reform and psychology of totalism“, Lifton interviewed former inmates of Chinese re-education camps. Trained as both a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, Lifton used the interviews to understand the psychological – rather than political or ideological – structure of totalitarianism. His next subject was Hiroshima; his 1968 book “Death in life”, based on extensive community interviews with atomic bomb survivors, won Lifton the National Book Award. He then turned his attention to the psychology of Vietnam War veterans and, soon after, the Nazis. In the two resulting books…”Return from war” And “Nazi doctors» – Lifton strove to understand the capacity of ordinary people to commit atrocities. In his latest book based on interviews, “Destroying the world to save it: Aum Shinrikyo, apocalyptic violence and the new global terrorism“, published in 1999, Lifton examined the psychology and ideology of a cult.

Lifton is fascinated by the breadth and plasticity of the human mind, by its capacity to contort itself to the demands of totalitarian control, to find justification for the unimaginable – the Holocaust, war crimes, the atomic bomb – and yet to recover and restore hope. In a century when humanity discovered its capacity for mass destruction, Lifton studied the psychology of the victims and perpetrators of horror. “We are all survivors of Hiroshima and, in our imagination, of a future nuclear holocaust,” he writes at the end of “Death in Life.” How to live with such knowledge? When does it lead to more atrocities and when does it result in what Lifton called, in a later book, a “species-wide settlement”?

Lifton’s great books, although based on rigorous research, were written for a popular audience. He writes primarily by lecturing into a dictaphone, giving even his most ambitious works a distinctive oral quality. Between his five major studies, Lifton published academic books, articles and essays, as well as two cartoon books: “Birds” And “PsychoBirds.” (Each cartoon features two bird heads with speech bubbles, such as: “All of a sudden I had this wonderful feeling: I am me!” “You were wrong.”) The impact Lifton’s work on the study and treatment of trauma is unprecedented. . In a tribute to Lifton in 2020 in the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, his former colleague Charles Strozier wrote that a chapter in “Death in Life” on the psychology of survivors “has never been surpassed, only repeated many times and frequently diluted in its power.” Everyone who works with survivors of trauma, personal or sociohistorical, must immerse themselves in its work.

Lifton was also a prolific political activist. He opposed the Vietnam War and spent years working in the anti-nuclear movement. Over the past twenty-five years, Lifton has written a memoir: “Witness to an extreme century» – and several books which synthesize his ideas. His most recent book, “Surviving our disasters“, combines reminiscences with the argument that survivors – whether of wars, nuclear explosions, the current climate emergency, COVID, or other catastrophic events, can lead others down the path of reinvention. If human life is not sustainable as we have become accustomed to living it, it is probably up to the survivors – the people who have stared into the abyss of catastrophe – to imagine and implement new ways to live.

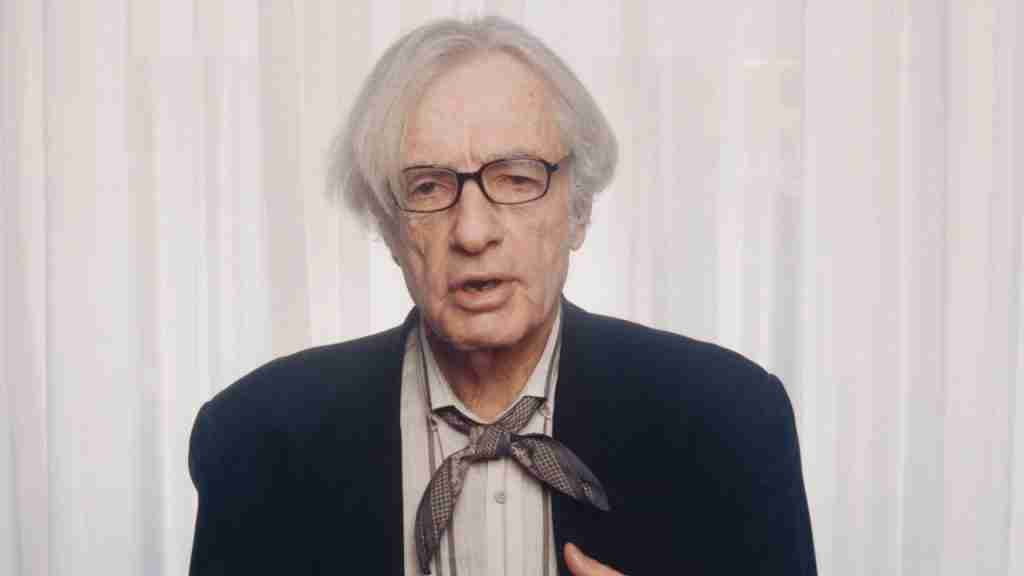

Lifton grew up in Brooklyn and spent most of his adult life between New York and Massachusetts. He and his wife, Betty Jean Kirschner, a children’s book author and open adoption advocate, owned a house in Wellfleet, on Cape Cod, which hosted the annual meetings of the Wellfleet Group, which brought together psychoanalysts and other intellectuals to exchange ideas. . Kirschner died in 2010. A few years later, at a dinner, Lifton met political theorist Nancy Rosenblum, who became a member of the Wellfleet group and his partner. In March 2020, Lifton and Rosenblum moved from his Upper West Side apartment to his home in Truro, Massachusetts, near the tip of Cape Cod, where Lifton, ninety-seven, continues to work every day. In September, a few days after the publication of “Surviving Our Disasters,” I visited him. The transcript of our conversations has been edited for length and clarity.

I would like to review a few terms that seem essential to your work. I thought I would start with “totalism”.

OK Totalism is an all or nothing commitment to an ideology. It implies an impulse towards action. And it is a closed state, because a totalist sees the world through his ideology. A totalist seeks to appropriate reality.

And when you say “totalist”, do you mean a leader or aspiring leader, or anyone else committed to the ideology?

Maybe one or the other. This may be the guru of a sect or cult-like arrangement. The Trumpist movement, for example, resembles a cult in many ways. And it is manifest in its efforts to appropriate reality, manifest in its solipsism.

How is this like a cult?

He forms a certain type of relationship with his followers. Especially his base, as they call him, his most fervent supporters, who, in a certain way, experience highs during his meetings and in relation to what he says or does.

Your definition of totalism seems very similar to Hannah Arendt’s definition of totalitarian ideology. Is the difference that this applies not only to states but also to smaller groups?

It’s like a psychological version of totalitarianism, yes, applicable to different groups. As we see now, there is a kind of thirst for totalism. This mainly comes from a dislocation. There is something in us as human beings that seeks fixity, precision and absoluteness. We are vulnerable to totalism. But this is more pronounced in times of stress and dislocation. Certainly, Trump and his allies call for totalism. Trump himself lacks the capacity to support a true, continuing ideology. But by simply declaring his lies to be true and embracing this version of totalism, he can hypnotize his followers and they can rely on him for all the truths in the world.

You have another great term: “thought-ending cliché.”

The thought-ending cliché is stuck in the language of totalism. So any distinct idea of totalism is false and must be abandoned.