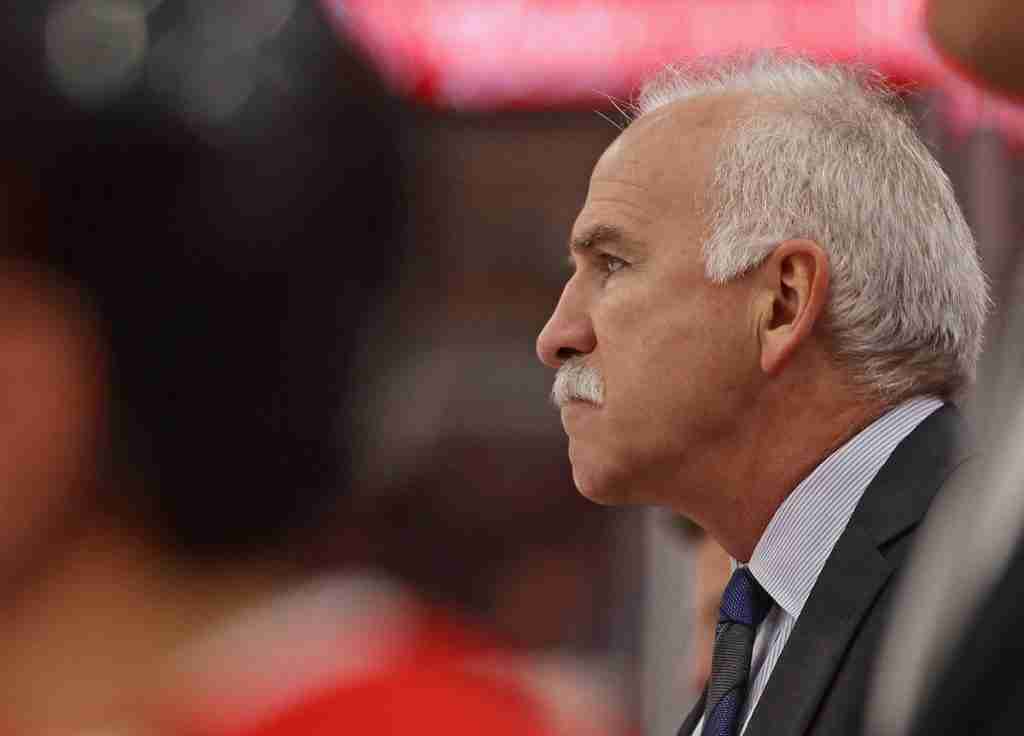

Then-Chicago Blackhawks head coach Joel Quenneville watches his team take on the Los Angeles Kings at the United Center in February 2018 in Chicago.Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images

If a media scandal is about breaking news you don’t want to see at the end of a busy day, what the NHL managed to pull off Monday was a media tornado.

It was the first day of player autonomy. It was a holiday in Canada, the only place where people care about player autonomy. It was the day four of the five players involved in the world junior sexual assault case were officially released by their teams.

Somewhere between the time Steven Stamkos was dumped by the Tampa Bay Lightning for a younger version of himself and Nashville gearing up for a championship run, an email was sent out from the league.

They were the three members of the Chicago Blackhawks management exiled to hockey limbo after Kyle Beach’s sexual assault civil case exploded in the league’s hands. The trio spent two and a half years without a character. They have now been readmitted to heaven.

Among them, Joel Quenneville is the clear favorite. He was once considered the best coach in the NHL, largely because the Blackhawks had some very good draft picks. All three are free to return to work in the league, but not right away.

They will not be able to accept job offers until after July 10.

Start by announcing the consequences. End with the real news. It’s clever.

Why now?

According to the league, it’s a mashup of trauma-focused words like “heartfelt remorse,” “increased awareness” and “self-improvement” based on “a myriad of programs.”

It has been difficult to find clear answers to this disaster, but the questions never cease.

But why exactly were they suspended in the first place?

The league has yet to find an answer to that question. The best it can offer is “an inadequate response” — even though it wasn’t the only one who knew about the matter, nor the only one who needed to do something about it.

How did the suspension process go?

No idea.

To be integrated ?

Same.

The three men held different positions with different responsibilities: head coach, general manager and vice-president of hockey operations. Why did they all serve the same sentence?

Look for me.

What has changed on the institutional level?

You guess, then I will and we will both never know.

What is known is that nearly 15 years ago, Chicago executives gathered in a room immediately after a playoff game to discuss Beach’s accusation that he had been sexually assaulted by the team’s video coach, Brad Aldrich.

When a law firm investigated the case, everyone had different memories of the meeting. Some denied understanding what was said, others said there was substantial talk. Quenneville recalled someone mentioning that “something might have happened,” but he didn’t know what.

I don’t know about you, but if the words “sex” or “assault” or any combination of them came up in an emergency work meeting, my internal radar would ring like a recess bell. But no one in Chicago remembered anything.

Due to their incompetence, Aldrich was allowed to leave the team voluntarily, without losing his Stanley Cup championship titles. In one of his subsequent postings, he was convicted of sexually assaulting a high school student.

That’s the North Star of this story: The men in charge of the Blackhawks had a responsibility to their community that they blatantly failed in, resulting in a preventable crime because to do otherwise would have interfered with winning a playoff series.

Two and a half years is a long time to be exiled from your professional tribe. There is no point in punishing without the possibility of redemption. If they repent, it is fair to consider their readmission. But not like this.

The NHL and the NHL Players’ Association managed to pin the heinous incident on three men who simply didn’t want to hear about it. Luckily, one of them was a celebrity.

Despite Beach informing her of what happened, the NHLPA managed to exonerate itself from the case. A law firm it hired concluded that Beach’s accusations were ignored due to a “lack of communication.”

Yet another question? How do hockey teams manage to get to the arena on time every night? It also involves communication.

Above all this is Commissioner Gary Bettman and the NHL’s command apparatus. In a well-run organization, the people at the top are responsible for all institutional failures, including those they knew nothing about. Otherwise, “I didn’t know” becomes an excuse for all sorts of administrative lapses.

If “I didn’t know” can work, no one will want to know anything, much less face it.

“I didn’t know” is what got the NHL into this mess. “I didn’t know” is why Aldrich was allowed to roam around looking for victims. And “I didn’t know” is how it ends — with no explanation from those in charge of the case about how it happened, how the penalties were determined and what steps were taken to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

The only thing that has been accomplished is eating sin. Quenneville & Co. have not been paid for the last two years, but they have had plenty to do.

The only recurring theme has been cynicism. At every stage, the first instinct of those in positions of responsibility has been to avoid the situation. How could they dump this matter on someone else’s property, where it would become someone else’s problem?

By accepting the blame, we prevent it from happening again. Systemic failures are institutional opportunities. How did the institution fail and how can it improve? We can’t undo history, but we can eliminate future excuses.

The way it ended – buried on the busiest day of the year for news, spread out over a period of time where potential hires will cause the least amount of trouble, the investigation process opaque from start to finish – shows that none of this happened.

If I were running a hockey club and saw a scandal coming my way, I would know now what the NHL wants me to do: send someone else to that meeting and make sure they never tell me what happened there.