BOSTON — Race is one of the defining issues in this country, and it’s not easy to talk about, but when we avoid it, it adds fuel to an already complicated fire.

For the first time since 1975, the NBA Finals have a black head coach on each sideline, with Dallas’ Jason Kidd taking on Boston’s Joe Mazzulla. Al Attles (Golden State) and KC Jones (Washington) finished last in a series the Warriors won 4-0.

Both Kidd and NBA Commissioner Adam Silver spoke about the significance of this accomplishment and the symbolism it may represent for the eternal struggle of black coaches in these leadership positions and what it means to them personally.

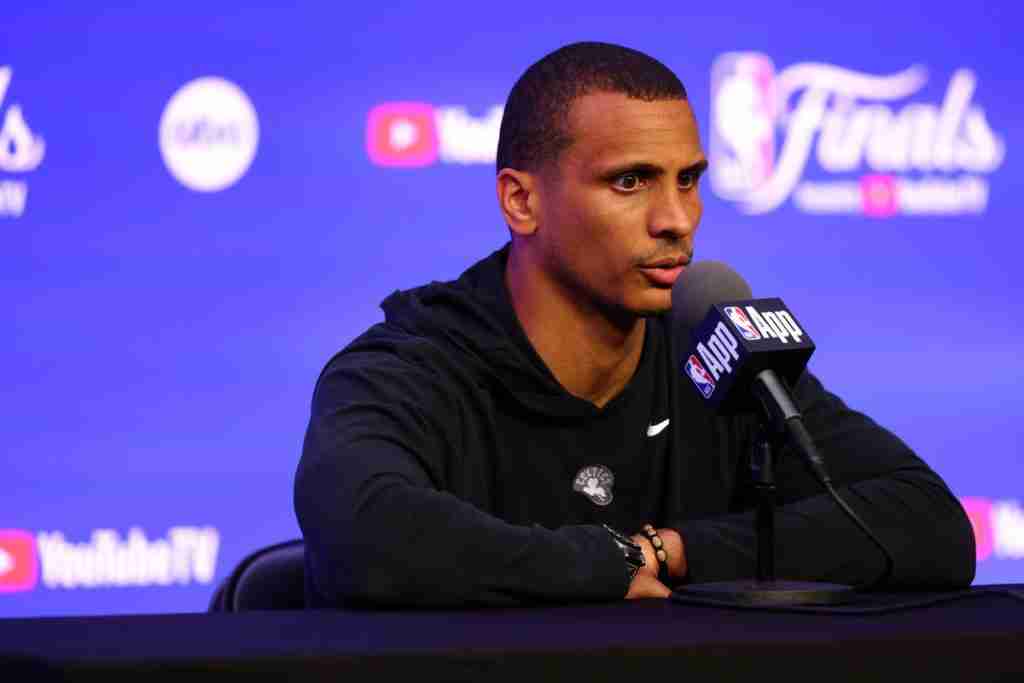

Mazzulla, who is mixed race, preferred to avoid it, giving more respect to his religion than his racial identity.

“I wonder how many of them were Christian coaches,” Mazzulla said when asked Saturday, essentially, if two black coaches in the NBA Finals meant anything to him.

There was a stunned silence in the room because that sounded like an awkward response, to say the least. Surprisingly, and this might surprise the Celtics coach, it is possible to be both black and Christian.

He didn’t explain that, he didn’t explain what it meant for him to be a Christian in that place. He brought religion to the party but didn’t choose to explore the conversation.

This could be seen as using this device to shut down any discussion on the topic at hand, simply a screeching halt. And to be fair, there was no follow-up question, just awkward silence – which might have been Mazzulla’s desired effect.

Mazzulla does not hesitate to jostle with the media, sometimes being very sensitive when he is questioned. He doesn’t seem rushed by the awkward silence, and perhaps he likes to embrace the strangeness in everything that comes with this professional sports ecosystem.

And he has referenced his faith when asked about things like the royal family coming to a Celtics game, so, at least publicly, he puts it forward and wears it proudly, regardless his value.

His relationship with his own racial identity is personal, but his answer certainly opens the door to further questions.

Especially because it’s Boston and the NBA’s workforce is predominantly black.

Boston’s relationship with black athletes has been rocky, dating back to its treatment of Bill Russell. One day, vandals broke into his house and Russell found feces on his walls and bed.

In the early 1990s, Celtics guard Dee Brown was arrested in nearby Wellesley with his fiancée in the passenger seat — under the guise of police searching for a bank robber, they claimed. And the guns were fired at Brown.

Today you will hear things in the stands that make you a little uncomfortable, even if nothing directly racist is said. Often it’s just a feeling.

It didn’t feel like a denunciation of Mazzulla’s darkness, so to speak. It wasn’t really the “I’m not black, I’m JO” moment; it just leaves room for interpretation.

“My faith is just as important as my race, if not more important,” Mazzulla told Andscape’s Marc Spears over a year ago. “To reach different people you have to be yourself and you can’t put yourself in a box. »

Boston is racially sensitive, and other blocs like to avoid any mention of race, so there is a risk that Mazzulla’s words on this big stage will be co-opted in ways he did not intend. Not just for the religious right, but also for bad actors who like to jump on statements like these to quiet conversations.

It happened to Jonathan Isaac in the Orlando bubble four years ago, when he used religion as a shield against discussions of police brutality against black people.

Many will defend Mazzulla’s response as a way to shift the very debate away from celebrating progress, if this moment is indeed a symbol of how far black coaches have come in the NBA when just a few years ago the numbers plummeted to the point of embarrassment (four Black head coaches after the 2019-20 season).

Before this recent cycle, there were 14 Black head coaches, and four of the top five teams in the Eastern Conference were led by Black coaches. JB Bickerstaff and Darvin Ham were fired recently after their playoff berths, while Brooklyn fired Jacque Vaughn and Washington fired Wes Unseld Jr. during the season.

So, while extremely competitive and extremely financially rewarding thanks to Monty Williams’ recovery plan, black coaches are typically the last hired, first fired.

“I think it’s important to have two Black head coaches in the Finals and, frankly, I wish there weren’t,” Silver said Friday afternoon at the inauguration of the Boys & Girls Club in Dorchester. “I think we’ve made tremendous progress there.”

Silver also hopes that with the number of women on staff increasing, it’s only a matter of time before a franchise selects a woman to lead one.

“I think people should take note of the fact that there are two African-American head coaches,” Silver said. “On the one hand, I want them to take note of it. But at the same time, I don’t want it to take away from the merit system that we have in terms of training. And it doesn’t take away from the fact that they coach these teams, of course, not because they are African-American, but because they are excellent coaches.

Mazzulla is an excellent coach, finishing in the upper echelon of Coach of the Year voting, including on this voter’s ballot. Who knows what box he checks when the question of race/ethnicity arises? But in this world, he is considered a black coach.

He doesn’t have to like it either, or show bad faith. It was a moment when Tony Dungy and Lovie Smith were the two black coaches in the Super Bowl in 2007, and it’s a moment here.

It’s not Mazzulla’s fault that the story is the story. But he should at least be aware of it. Ignoring race in these areas is not progress, because it can infer that considering someone Black means something negative. Color blindness is impossible, and seeing someone’s blackness or black experience as positive could be the ultimate sign of progress.

“It’s always a discussion, because it doesn’t happen often,” Kidd told Yahoo Sports with a laugh Saturday afternoon. “In 75, I was 2 years old. Joe was not born. So I think that’s huge. It just shows how far we’ve come, but we also have a ways to go. I think that means something that we just have to continue to build on.

Silver is looking at the pipeline of Black assistant coaches, which means there are more opportunities when openings arise. Kidd, while finding stability in Dallas, knows what it’s like to be fired, even with a winning record in the middle of a season.

“It starts first and foremost with ownership. We need to talk about ownership and higher positions,” Kidd said. “So when you look at ownership and general managers, that’s where it all starts. Being able to have people who can say, “We’re going to build this.” We’re not going to fire anyone after one or two seasons. This means there is a plan. It starts higher up, not with the coaches.

Kidd spoke about the added responsibility of coaches, and for black coaches, it’s an added burden that is often heavier than that of basketball.

“Coaches have a responsibility to do their best to win, but I also think sometimes what doesn’t get considered is what happens off the field,” Kidd said. “To develop better men as they advance.” And I think Pop (Gregg Popovich) said this in his Hall of Fame speech…we’re always measured by wins and losses, but the beauty of everything about coaching is that ‘They come back to see you once they’re finished. playing. You know, I think it’s something that’s not measured by, you know, hiring and firing.

Jaylen Brown doesn’t hesitate to join in the discussion when it arises. And while he’s well-versed in Boston’s history, he’s committed to the franchise and invested in the community.

He’s not afraid of the subject and seems endlessly curious – it seems very clear that he and Mazzulla have different experiences, different perspectives and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Mazzulla has the right to embrace his religion, to rely on it to help him in his professional and personal approach. He has the right to look in the mirror and see not first a black man, but a Christian with strong convictions.

But if he’s stopped in Boston, the police will see his last name on his license, but before they find out anything else about him, they’ll first see a black man.